Highlights from the book I Am Not a Monk “Sponging Off” Buddhism, by Venerable Master Hsing Yun

Only Setting the Tone and Not Becoming the Master

What Are Some Innovations I Have for Buddhism

It seemed that I had to do everything for Buddhism. For Buddhism, I have to only set the tone and not become the master, hand over my physical body to the temple and give my life to the Dharma protectors, heavenly beings and nagas, and making the aspiration to head out for Buddhism, striving to move Buddhism toward humanity and society. It seemed then that I suddenly saw people in the tens of thousands who were waving at me. I must propagate the Dharma for the benefit of sentient beings, and usher in a new set of circumstances for Buddhism.

Before I joined the monastic order at the age of twelve, I intermittently attended some classes at a private school, but altogether it did not exceed more than two months.

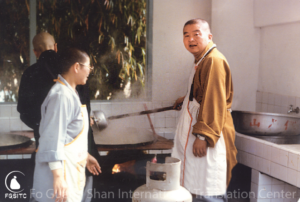

After joining the monastic order, I lived entirely in a conservative monastery for nearly a decade. Occasionally, a teacher would come to teach a class, but that did not happen too many times. The majority of my time was spent in serving through physical labor.

As for these thoughts and beliefs of mine, essentially no one demanded them of me or forced them upon me. I just naturally came to realize that in this new age, survival requires adaptation to the changing environment. Within the age-old Buddhist college, there was basically no opportunity for innovation. Thinking back on my ten years of extremely inflexible temple life, every day was simply spent lining up, bowing, kneeling, cutting firewood, carrying water, and so forth. Our discipline master did not allow us to read newspapers, use fountain pens to write characters, or read books outside the field of Buddhism. However, I was not able to understand the Buddhist classic sutras and related books, and that was how those long ten years, the years of my youth, were spent.

When I was seventeen or eighteen, I entered the Qixia Vinaya College and began my studies. I was very fortunate that my teacher sent me to the library as its administrator responsible for taking care of the books. The library had a collection of books from the library of a teacher’s college. The teacher’s college had been disbanded during the Sino-Japanese War. No one wanted the school’s books, so we moved the books back to the temple, even though nobody wished to borrow or read them.

I made use of this opportunity to read quite a few books then. At the time, I felt as if I had just been awakened from a dream to discover that the human world had such treasures.

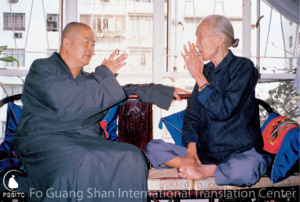

Later on, I learned about Venerable Master Taixu, and my classmates said he was the leader of New Buddhism. I had no idea what was meant by “New Buddhism,” but I did know that Buddhism needed reform and innovation. Buddhism could not merely be in accord with the truth; more importantly, it had to be in accord with circumstances.

At the age of nineteen or twenty, I was studying at the Jiaoshan Buddhist College, and I saw Venerable Master Taixu returning to the capital after Chinese victory in the war. At the time, it seemed as if I were seeing the Buddha, and I could not help but hasten forward and join my palms together to prostrate to him. He looked at me with a smile, and responded with, “Good! Good! Good!” Then he walked past me. Even though the time was short, I was very moved and vowed at that moment to spend the rest of my life being “good.” Slowly, I came to understand the orientation of New Buddhism and its goal.

Consequently, in the spring of the following year, the early spring of 1949, I travelled to Taiwan through Shanghai.

I did not have anything when I first arrived in Taiwan. Besides the clothes I was wearing, the only other possession I had was my identity card and the ten silver coins with Yuan Shikai’s portrait on them given to me by my master. That was how I began my life in Taiwan.

During those first two years at Chungli and Hsinchu, I read quite a few books on literature, history, and philosophy. At the same time, I gained some insights in the area of Buddhist studies.

During this period, I wrote some short articles and also published a few poems, such as “The Great Buddha,” “Bells, Gongs, and Wooden Fish,” and “Star and Cloud.” Based on my experience of having read several books, I began my career of teaching and editing magazines.

I arrived in Ilan during the first lunar month of 1953. When I was in mainland China, I thought about how I would work for Buddhism in the future.

The Venerable Master says that we should love children, for they are the future of our nation. Pictured is the Venerable Master shaking hands with a child attending an outdoor learning curriculum at the Buddha Museum

June 30, 2012

I thought I would write a newspaper posted on walls along the street for publicity, distribute Buddhist fliers, give street lectures, and ensure that Buddhism would be drawn closer to the multitudes. I would do the work of propagating the Dharma in several different ways.

However, Ilan was a small and backward place, and I was significantly inadequate in economic conditions, but being there was exactly what sparked the new ideas that spurred me on, urging me to light a new kind of fire for Buddhism. Therefore, I established a Buddhist choir and organized youth groups, student associations, and children’s classes. I also instituted an after-school program for the arts and a Dharma mission.

Even though I dared not say that I possessed any qualifications, the only thing I could rely upon was that I had aspiration and strength. The more I aspired to do for Buddhism, the more new thoughts and ideas sprang forth from my mind in an endless stream.

These innovations endured criticisms from Buddhist circles at that time, to the point where I was looked upon as a great scourge. Despite this, I had no time to think too much about it, as I was single-mindedly focused on devoting the mental and physical strength I had to Buddhism, so Buddhism would adapt to the modern world. Therefore, I made some reforms and innovations step by step. To this day, haven’t Buddhist choirs, recorded discs, DVDs, TV Dharma teachings, family Dharma services, and A Discussion of Chan over A Vegetarian Meal been promoted in temples and monasteries? This piece notes a few of these items.

- Music

As for singing, although I am unable to carry a tune, I know that music is a language without borders, and it is the most effective and efficient means for propagating the Dharma. When I first arrived in Ilan, I organized a choir, and did it not guide many young people to come in droves? Within the twelve divisions of the Buddhist canon, the sutras in prose style are universally applicable, while the repeated verses and verses as poems and songs are also very important. All the Buddhas have devotees in all directions singing their praises; the masses in the hundreds of thousands also hope to hear the melodious sound of this singing.

I saw how enthusiastic the response was, so I expanded upon the influence of the singing group. During gatherings for the Buddhist Chanting Service, instead of the dedication of merit at the end of the traditional arrangement, we would use the singing of a song or a prayer; this moved everyone even further.

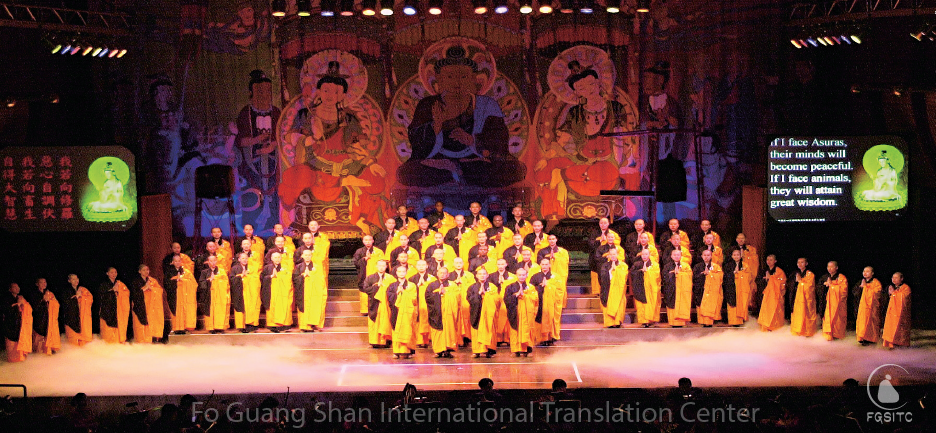

Fo Guang Shan Buddhist Monastic Choir performing at the world-renowned Lincoln Center in New York, a first in Buddhism.

October 19, 2001

I also invited some professional teachers to transcribe the notation for Buddhist verses into the numbered musical notation form. After we had that, everyone felt that the verses of early Buddhism could be sung quite easily.

Under very difficult circumstances, I used the pure wealth from the donations of devotees to make audio tapes and even records, which expanded the scope of influence for the songs. Isn’t the radio the place with the most singing? Consequently, I further promoted Buddhist songs for broadcast on the radio, enabling more people to hear them. At the time, I also created programs for the Broadcasting Corporation of China and the Ming Pen Broadcasting Company.

In short, no senior monastic came to oppose or praise this work during my time in Ilan. There were only the young people who came to sing. In my mind, these songs belonged to the youth and were for them to sing. There was no need for me to become discouraged because of different opinions. I thought I ought to offer the young people appreciation and encouragement.

- Festival of Light and Peace

I grew up in the barren and poor Northern Jiangsu Province. I remember that every year during the Spring Festival, a mile from my hometown, the temple to the local village god would hang up lanterns. In that time of darkness without lights, being able to hang up a lantern was already an extraordinary lantern festival.

As evening drew near, the people in the village would happily say to the young and old in tow, “The lanterns are up! Let’s go see the lanterns!”

Thinking about it now, these were only a few simple lanterns and nothing more, but they brought joy and hope to everyone.

Fo Guang Shan Festival of Light and Peace.

Photo by Zheng Tiaoyi

Therefore, during the Spring Festival, besides ensuring that the public can come to Fo Guang Shan to pay homage to the Buddha, I also arrange for the Festival of Light and Peace to be set out for everyone to view and enjoy. This allows everyone to light a lantern in a prayer for blessings.

In Buddhism, the lamp represents light, which mainly refers to how we can illuminate the lamp of our own mind.

Back then, I already thought about how the public could light a lamp to be offered before the Buddha, serving as a symbol of illuminating the lamp of their own mind. It was unfortunate that the temple where I first resided did not have a place to display offering lamps. Even if one were to light a lamp, one would not know where to put it as an offering.

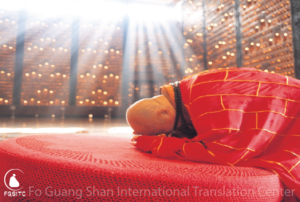

After Fo Guang Shan was built, we began to promote the lighting of Peace and Safety Lanterns. Everyone could light a lamp of their mind before the Buddha and then hang a red-colored lantern up along the corridor. The beauty of a single lamp would allow the believer to interact with the Buddha in the light of its glow.

I told the devotees at Fo Guang Shan’s Light Offering Dharma Service, “Today, it is you who are illuminating the entire world; it is you who are giving warmth to the world; and it is you who are dispelling the darkness. With your lighting of a lamp here, the Buddha can see everyone’s intentions to make an offering. The visitors who have come from various parts of the world will also see your lights and receive your merits. It is exactly as the Chan School states: ‘A room shrouded in darkness for a thousand years is instantly illuminated by a single lamp.’” By illuminating the lamp of the mind, a person’s entire life can brighten.

Chapter subheadings:

- Music

- Children’s Classes

- Cloud and Water Mobile Clinics and Mobile Library Trucks

- Festival of Light and Peace

- Pearls of Wisdom: Prayers for Engaged Living

- Art Galleries

- A Food Fair

- Concluding Remarks

The Author’s Preface, Forewords, Afterword, and Chinese Editor’s Remarks are available to read online.