Highlights from the book I Am Not a Monk “Sponging Off” Buddhism, by Venerable Master Hsing Yun

Am I Really like a Monk?

Given that I have become a monk,

I have placed demands upon

myself. My sense of leaving the secular

and focusing on the path must

surpass others; my sense of self restraint and

doing for others must be

strengthened. I must learn to endure

disadvantage, and I must let others

gain some advantage at my expense; I

must learn how to be patient and how

to undergo adversity. This is all as it

should be.

Since joining the monastic order at a young age and over the course of my eighty years as a monk, I have constantly asked myself, “Am I really like a monk?”

Upon shaving my head and putting on my monastic robes, I was clearly aware that I had joined the monastic order and become a monk. However, I constantly examine myself: “Am I really like a monk?” At first, I examined my own mentality regarding my faith: “Do I really believe in Buddhism?”

There is no question that I already had the foundation for faith from the time I accompanied my maternal grandmother as a child. Although it was not very pure or transcendent, my faith was most certainly in Buddhism, not in some heretical doctrines.

- Aspiring to Work: The Development of My Self-Education

After joining the monastic order, I further asked myself, “Am I like a monk when I talk? Am I like a monk when I walk? Are all of my actions and conduct like those of a monk?” I paid attention to my own bearing and deportment from time to time, that I must “stand like a pine and walk like the wind.” In eating a meal, I must be like “a dragon swallowing pearls, a phoenix nodding its head.” In speaking, I must speak “truthful and compassionate words.” I must be as a monk should be.

Upon reaching adulthood, my knowledge of the world had increased, my thinking had increased, and my desires had also increased. Thus, I thought to myself, “Can I remain a vegetarian my whole life?” In being a monk, one must certainly be a vegetarian. This is not a problem in that before I had joined the monastic order, I already had the concept of vegetarianism.

Furthermore, being a monk means that one should not go out into society at night, watch and listen to music and dance, or laugh merrily and joke around as people in society do. I did not think that would be difficult either because as a child I always behaved myself at home; I never got into fights with the other children, and I never scolded other people. Since I liked doing housework and acting dutifully toward my parents, I did not think it would be a problem for me to become an obedient and contented monk who honored his teachers within the Buddhist tradition. I thought, “I can be a good monk.”

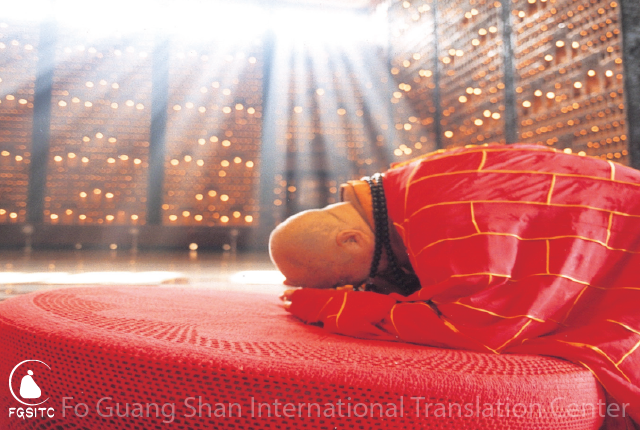

The Venerable Master paying homage to the Buddha in the Main Shrine, Fo Guang Shan.

Photo provided by the Historical Museum of Fo Guang Shan

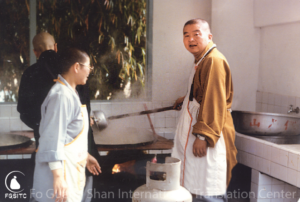

I also considered that in becoming a monk, one should make a resolve and be willing to undertake some hard work, such as cooking, gathering firewood, carrying water, guarding the monastery, and patrolling the dormitories at night. “Can I endure a life with so much hard work?” I asked myself. But this was not a problem either; I grew up in a poor family since childhood and was accustomed to a life full of suffering.

This kind of energy was in my intrinsic nature, and I felt that I could be still a good monk.

As I slowly grew up, I further considered how a monk must have knowledge, be able to expound ideas through writing, and benefit sentient beings by propagating the Dharma. I wondered, “Am I able to do these?” When I was young, I thought about how I would found a university and run a newspaper in the future, but I knew that it was merely a dream because it was impossible to realize given my circumstances at the time. However, we must have a dream. This aspiration that I cherished in my heart remained unknown to anyone else. If I were able to realize such a dream, then I would really be a monk who propagates the Dharma for the benefit of sentient beings.

However, being a monk, I must be able to chant and play the various kinds of Dharma instruments. In this case, I knew of my shortcomings in these areas, but I was completely oblivious that I was tone deaf. It wasn’t until I learned of it from someone else that I realized how serious things were. Since the chanting of my other classmates was especially esteemed and well received by others, as I had no sense of musical rhythm and had no voice that could carry a tune, I could not help but feel inferior at that time. My inability to be as good as those many classmates and senior schoolmates always left me feeling a measure shorter in stature compared to them.

In retrospect, I thought it didn’t matter that much, as there are many ways to be a monk. As long as I am able to abide by the rules of being a monk, and to receive as well as uphold the precepts, then I may engage in cultural, educational, and charitable work. I need not remain only within the shrine conducting sutra chanting and repentance services or playing the Dharma instruments. I thought that this was not necessarily a shortcoming, for I firmly believed I could become a cultural monk, an educational monk, and a charitable monk.

- Leaving the Secular for the Spiritual, Insisting upon Self-Restraint and Doing for Others

Given that I have become a monk, I have placed demands upon myself:

My sense of leaving the secular and focusing on the path must surpass the resolve of others; my sense of self-restraint and doing for others must be strengthened. I must learn to endure disadvantage, and I must let others gain some advantage at my expense; I must learn how to be patient and how to undergo adversity. This is all as it should be.

Although Buddhism was very conservative at the time, I thought in the future if I had the opportunity to find a Buddhist leader, I would follow him and undertake the building, reform, and development of a new Buddhism, as well as this new Buddhism’s guidance, to benefit the lives of the humanistic devotees. I thought that I should have this energy, aspiration, and resolve. I felt assured of myself that I was able to be a good monk.

Am I really like a monk? I am certain that I will be like a monk.

But later on, I saw how some monks wore their robes untidily, and felt that they were not like monks; I saw that their diets were not vegetarian, and I felt that they were not like monks; I saw that they frequently returned to their secular families, and were unable to separate themselves from secular life, so I felt that they were not like monks. Within Buddhism, there are many people who are like monks, and there are many others who are not like monks. As long as a person wears a monastic robe, they are “monkish” (having the external appearance of a monk). Are ordinary devotees able to discern who is “monkish” and who is a “monk”? In my mind, devotees will also find it difficult to tell the difference.

In my mind, joining the monastic order has nothing to do with the formality of shaving the head or the donning of monastic robes at all. What is most important is that the “mind” must leave home to join the monastic order. In particular, one’s faith and conviction in Buddhism, as well as one’s life in the future, have to convince the larger community that one is a monk. Only in this way does one “manifest the form of a monk.”

Chapter subheadings:

- Aspiring to Work: The Development of My Self-Education

- Leaving the Secular for the Spiritual, Insisting upon Self-Restraint and Doing for Others

- A Mind Devoid of Sentient Beings Is like an Insect on a Lion’s Body

- Conduct and Mentality Must Adhere to the Dharma

- Helping the Buddha Propagate the Dharma and Transform Sentient Beings: Dharma Waters Nourish the Masses

- In the Self-Reflection of Monks, the Dharma Will Surely Flourish

The Author’s Preface, Forewords, Afterword, and Chinese Editor’s Remarks are available to read online.