Highlights from the book I Am Not a Monk “Sponging Off” Buddhism, by Venerable Master Hsing Yun

My Reflections on Venerable

Master Taixu’s Fiftieth

Birthday Poem

In fact, what I have enjoyed the

most in my reading, and it could

be said that a piece of writing that

has had an important influence upon

my life is the poem “Thoughts on My

Fiftieth Birthday,” written by Venerable

Master Taixu during his visit

to India when the lay Buddhist Tan

Yun-shan, Chairperson of the Institute

of Chinese Language and Culture

at Visva-Bharati University held

a celebration for his fiftieth birthday.

Everyone celebrates their birthday on the day they were born, or it may be called a “birth celebration.” In particular, all the birthdays that mark decades are especially important, such as ten, twenty, sixty, eighty, and ninety years of age.

From my birth up until now, I have not been someone who enjoys celebrating birthdays, nor do I remember my ordinary birthdays.

However, I can recall a few of my birthdays that marked a decade, and most of those were celebrated with the help of others, so I do have some memories that I will talk about here just for everyone’s amusement.

- No Birthday Celebrations, No Feelings of Self-Importance

The year I turned thirty years old, I was already in Taiwan. The wife of General Su Li-jen [1900–1990], Madame Sun-Zhang Ching-yang, along with several like-minded friends, had established a weekly periodical called Awakening the World. Since they could not find anyone to do the editing, they looked to me for help.

Later on, they heard about my thirtieth birthday, marking how one “stands firm” according to Confucius. They made a special effort to lay out a table of vegetarian food for me. All the utensils, spoons, and chopsticks were made out of gold. Madame Sun’s two large cases of golden tableware had never been used before, but in order to express the importance I held for her, she had the whole set brought out to celebrate my birthday. But I was not pleased at all. Why? I did not feel that I was that important. However, in the face of so many people senior to me, I found it difficult to turn them down, and the event passed in a baffling muddle.

My fortieth year came with the founding of Fo Guang Shan, and with all the bustling about at that time, I did not remember which day marked my fortieth birthday.

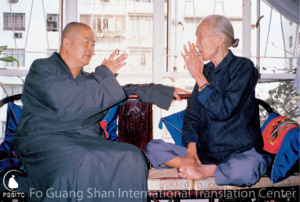

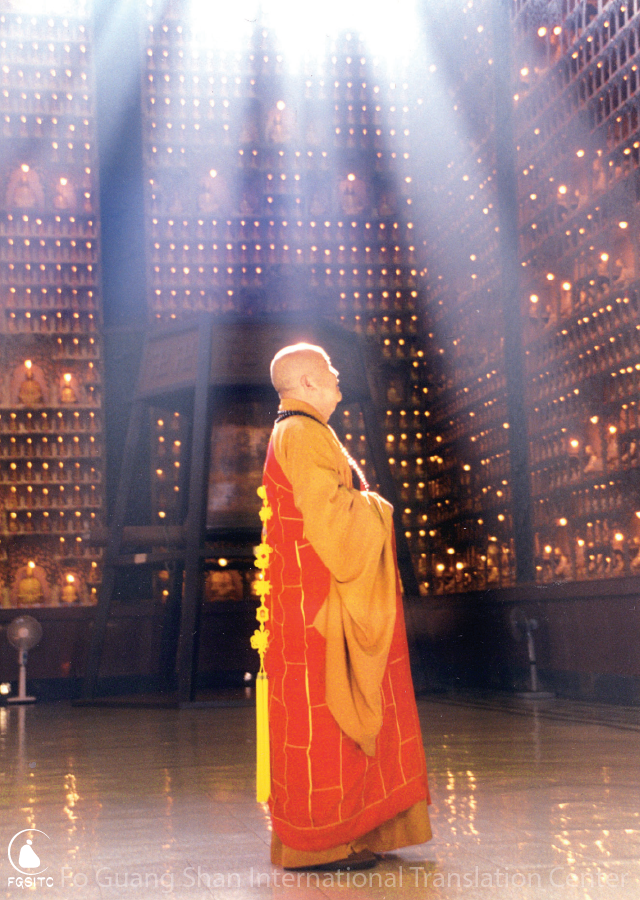

The Venerable Master at his sixtieth birthday celebration, with over one thousand devotees of the same age-group.

Photo provided by Historical Museum of Fo Guang Shan, July 22, 1992

When I was fifty, Fo Guang Shan was at an important stage in the building project. I was so busy that I forgot all about birthday celebrations.

By the time I was sixty, the Pilgrim’s Lodge, the Buddhist college, and the Main Shrine were all more or less completed. According to the monastic administrative system, I should have stepped down from my position at the age of fifty-eight.

- Holding a Long-Life Celebration, Blessing the Elders on Their Sixtieth Year

In that year, Venerable Hsin Ping, my disciple who succeeded me as abbot, was determined to hold a sixtieth birthday celebration for me. The other disciples and devotees also repeatedly followed his lead in making this request. There was no way I could refuse in the face of so many people, so I had no choice but to say, “If you are able to find one thousand people who are sixty years of age and gather them together at Fo Guang Shan, then I will celebrate my birthday with you.”

I do not know how they managed to invite them, but there were actually one thousand and three hundred individuals, all sixty years of age, who had come to Fo Guang Shan. In the past when they talked about celebrating my birthday, I always felt unhappy. But on that day, I was not upset at all, for I felt that being together with more than a thousand seniors who were also sixty years old made me feel like it was a grand affair. At the same time, I could also happily bestow blessings upon those many elders on their sixtieth year who have lived half a century.

When I was seventy years old, I was probably traveling abroad, and I do not know how I spent that birthday, either.

I was at Hsi Lai Temple in the United States the year I became eighty years old. I remember one day as I was eating rice porridge, I suddenly remembered that it was my birthday, and it was not until then that everyone remembered I had turned eighty. No one knew what would be the best thing to do; at which point I said, “It is alright! Rice porridge is also a suitable meal for old folks.” This too is a kind of beautiful reflection.

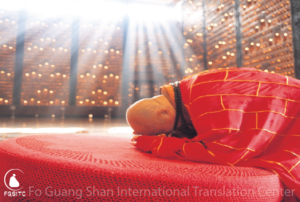

This year (2016), I have reached the age of ninety. Since I dared not disturb anyone, I made a special effort of hiding myself away at Yixing Dajue Temple, the seat of my lineage.

I spent a day in a quiet room for a secluded retreat, chanting sutras, sitting in meditation, pondering deeply, and contemplating silently.

Photo by Venerable Hui Yan

This was the Buddhist Mother’s Day of Suffering, a parental kindness so difficult to repay. How could I hold a celebration for myself?

The Buddha’s kindness in particular is so vast and expansive, and there is no way I can recompense it. How dare I speak of longevity? All I could do on that day when my mother suffered strenuous hardship was to make a wish for her and pray for her.

That afternoon, since the People’s Publishing House in mainland China had published a simplified character edition of my new book, Humanistic Buddhism: Holding True to the Original Intents of Buddha, a publication announcement was held at Dajue Temple. More than three hundred college presidents, professors, and scholars from many education circles came. No one mentioned my birthday, so I felt very happy.

Additional chapter subheadings:

- New Clothes at the Age of Ten Were Burned by Mosquito-Repellent Incense and Discarded

- No Birthday Celebrations, No Feelings of Self-Importance

- Holding a Long-Life Celebration, Blessing the Elders on Their Sixtieth Year

- A Long Verse Expressing Thoughts as a Means for Cultivating the Mind

- Reforms in Defense of Buddhism Emulating the Example of Spiritual Conduct

- The Dedication of Mind and Body Given to Sentient Beings in the Universe

- Following the Bodhisattva Practice, Vowing that Buddhism Depends upon Me

The Author’s Preface, Forewords, Afterword, and Chinese Editor’s Remarks are available to read online.