In the early days of Buddhism, how did monastics observe the Way and live their lives? As the daily lives of these monastics were not one of material things, emotional ties, or sensory pleasures, they led a lives of few material things and cool emotional ties.

The world within their heart was pure and their spiritual life was forever lasting.

In more concrete terms, their personal belongings were limited to three garments and one bowl. They only ate one meal a day, and they often slept under trees, along river banks, or even by burial grounds. Then there was the method of “discipline cultivation,” which involved an enormous amount of solitude.

The goal of discipline cultivation was to become unperturbed by the trials of life through discipline or even ascetic practices. They were not after present enjoyment and thus worldly temptation did not have a hold on them. They often shunned crowded and noisy places and were most keen on attaining the eternal peace of nirvana. Unfortunately, some people today just want to copy the lifestyle of these arhats in appearance, but not in practice. They want to remove themselves from communities and yet long to live in worldly comfort. This later lifestyle is not what we mean by cultivation.

The elder Mahakasyapa was one of the foremost disciples of the Buddha. He was most diligent in his practice of discipline cultivation. Through a life of frugality, he wanted to purify his body and mind, to free himself from the shackles of worldly worries, and to attain the ultimate Buddha-wisdom.

One day, the Buddha happened to notice Mahakasyapa was well advanced in years and advised him, “You really need not live such an ascetic life. You can return to the Jetavana Monastery and be the head monastic.There, you can lead the assembly in practice. This way, you can still achieve your goal of purifying your mind of worldly cares and desires.”

Mahakasyapa replied to the Buddha, “Lord Buddha, I really cannot do as you have suggested. I am here to practice discipline cultivation, and I want to set an example for generations of Buddhists. I want them to know that ascetic practices can help us sharpen our will, strengthen our faith, and boost our spirit. We need to find our hearts and minds and be masters of them. This way, we will be in the company of all Buddhas.”

Worldly living measures happiness by how much one owns; transcendental living builds happiness on the freeness of not possessing.

Possession is like a piece of baggage; it can be burdensome. Not possessing is boundless and limitless. Though these enlightened individuals did not possess much, they had the whole world to enjoy.

The material life of the sangha was limited to the basics. When the Buddha’s aunt offered the Buddha two garments that she herself had made, the Buddha only took one and asked her to offer the other one to a bhiksu. The life of the sangha emphasized self-reliance and mutual support. When older bhiksus could not see well, the Buddha helped them thread needles and mend clothes. When some of them fell ill, the Buddha prepared medicine for them and helped them bathe. The life of the sangha was demanding and called for self-motivation.

The Buddha often encouraged his disciples to travel as much as thirty miles to receive an offering. The sangha sometimes traveled many miles to teach the Dharma. From our standpoint, such a life may seem harsh, but these enlightened individuals were not the least bothered by the meager conditions they lived in. Regardless how trying the circumstance, it was a means to observe the Way. The arhats did not make the distinction of possessing and not possessing, far and near, or hardships and comfort. They looked at each of these qualities with equanimity.

Now, it is different with lay people. Everyday, you have to think about what you should wear for the day. If you want to wear red, you may even have to think about which shade of red looks good on you. All those decisions! Tomorrow, when you come to attend the lecture, you may want to wear a color other than red. Which color? Green, maybe.

Let me give you another example. In the kindergarten school that we have opened, we just hired a few young ladies to be school teachers. Their salary was three thousand dollars a month. In the school, there are also a few monastics working as teachers. As monastics, they are only paid a hundred dollars a month. Strangely enough, I once heard a salaried teacher asking a loan from a monastic. What is enough? Is three thousand dollars enough? Is a hundred dollars enough? To make a lot of money does not necessarily mean happiness; to make a mini amount is not necessarily bad either.

To enlightened individuals who have renounced their attachments, all the happenings in the world seem like fleeting smoke or floating clouds, leaving not a trace in their minds.

They remain unperturbed by worldly phenomena and are not slaves to desires. They look at relationships coolly, and everyday they live their lives simply, peacefully, freely, and harmoniously.

To live transcendentally does not mean we have to live apart from people. When we live and function in our homes and society, we can practice transcendental living by remembering four things.

First, we cannot let wealth and fame dictate what we do.

Second, our love for others should not be possessive and demanding in nature.

Third, we should not become attached to power and position.

Fourth, we should not focus on self versus others, or what we like versus what we dislike.

If we can live in this world in accordance with these four points, then we will taste the joys of a transcendental life.

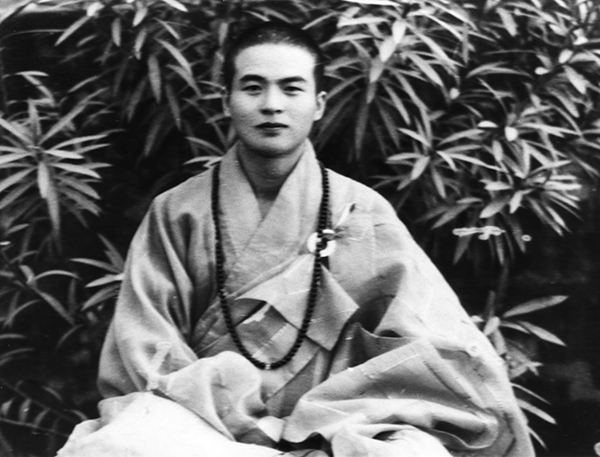

From Worldly Living, Transcendental Practice, written by Venerable Master Hsing Yun.